In the autumn of 1918, Edward Kidder Graham, the University of North Carolina’s president, sought to calm worried parents as the Spanish flu rapidly spread. Despite his assurances of safety measures, Graham fell victim to the flu and died, followed by his successor Marvin Hendrix Stacy two months later.

Similar turmoil plagued many universities during the 1918 pandemic, as detailed in a forthcoming book on higher education, “From Upheaval to Action: What Works in Changing Higher Ed,” by Arthur Levine and Scott Van Pelt. The book explores the parallels between the Spanish flu and Covid-19 impacts on colleges.

Related: Our free weekly newsletter keeps you informed about school and classroom research.

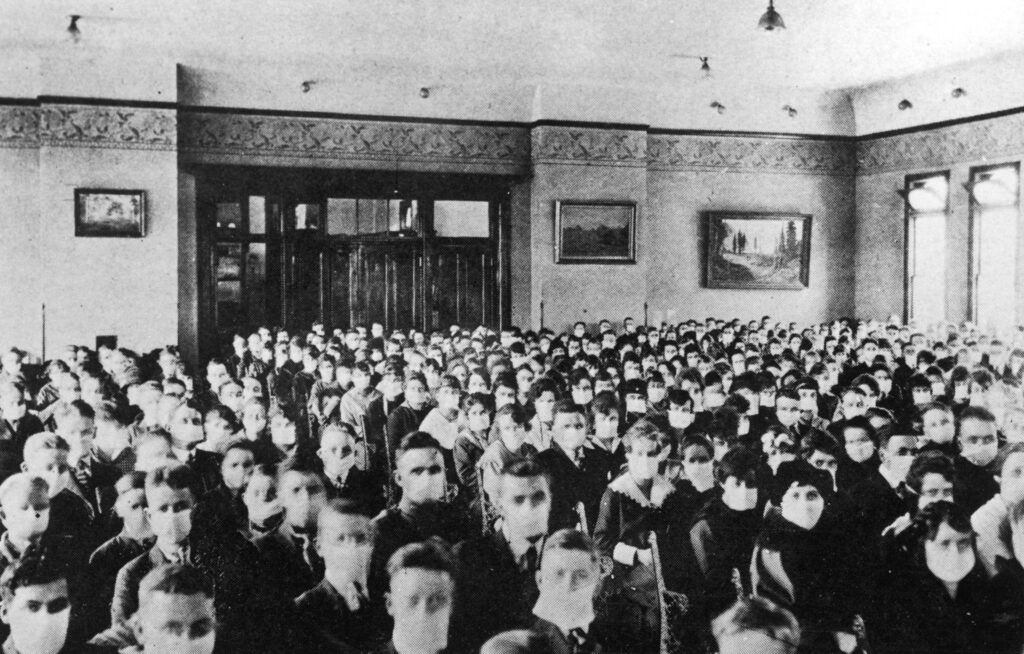

During the 1918 pandemic, Harvard canceled lectures exceeding 50 students, and Yale closed its campus after partial measures failed. Many urban colleges temporarily shut down, canceling or postponing orientations and commencements. Iowa State University converted gymnasiums into makeshift hospitals, and the University of Michigan turned dormitories into quarantine facilities when infirmaries overflowed.

The pandemic’s second wave proved deadlier than the first, eventually killing about 675,000 Americans when the U.S. population was around 100 million. This death toll was nearly twice the proportional rate of Covid-19, which claimed approximately 1.2 million lives in a much larger population. The Spanish flu primarily affected young adults in their 20s and 30s, critical ages for college enrollment and faculty positions. Levine argues higher education failed to support this generation’s academic, social, or psychological recovery.

Instead, higher education moved on. “We essentially aged out of it,” said Levine, speaking at the American Enterprise Institute about higher education’s challenges. Correspondence courses expanded, and in 1922, Penn State introduced radio for instruction, marking early forms of remote learning. Female enrollment increased, especially in nursing.

Related: Many college students still take online classes post-reopening

The pandemic and World War I disrupted education, leading to a depleted and altered student body known as the lost generation. Their disillusionment, captured by writers like Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, characterized the era. The Roaring Twenties, Levine suggests, were more a counterreaction than a recovery, soon overshadowed by the Great Depression.

Levine doesn’t romanticize the past. “Everything I’ve read makes it sound like the Spanish flu combined with World War I may have been a harder slog,” he said. “So many lives were lost — not only students but faculty and staff. Mental health resources were primitive.”

The current situation reveals unsettling parallels but significant differences. Today, over 60% of young adults attend college, making higher education integral to economic mobility and social identity. Covid-19 not only disrupted education but also imposed prolonged social isolation, complicating recovery amidst social media’s influence.

Declines in enrollment following Covid echo those of the Spanish flu era. However, simply replacing lost cohorts is no longer feasible. The consequences of disruption in today’s mass higher education system are broader and more visible.

The lesson from the Spanish flu is not that recovery is inevitable, but that institutions previously waited it out. A century ago, this approach had limited impact. Today, the costs may be higher, given the larger and more psychologically vulnerable young adult population.

Contact staff writer Jill Barshay at 212-678-3595 or barshay@hechingerreport.org.

This story about the Spanish flu’s impact on universities was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on education inequality and innovation. Sign up for Proof Points and other Hechinger newsletters.

—

Read More Kitchen Table News