Approximately 14 billion years ago, the universe emerged with the Big Bang, propelling matter and energy and paving the way for galaxies and planets, including Earth. While the universe’s composition includes stars, planets, and galaxies from the periodic table, dark matter and dark energy remain elusive yet significantly influential.

Dragan Huterer, an associate chair and professor in the Department of Physics at LSA, specializes in theoretical cosmology, exploring the universe’s grand concepts like the Big Bang theory, dark matter, and dark energy. Unlike astrophysics, which examines celestial objects, cosmology delves into these overarching ideas.

“We can’t answer why the Big Bang occurred or what existed before it,” Huterer said. “But one of humanity’s most amazing feats is that we know what happened just moments after it occurred. In fact, we arguably know more about the Big Bang aftermath than we do about the human brain, despite being able to physically study the brain. That’s a paradoxical thing.”

Over a century ago, scientists observed the universe’s expansion, soon discovering dark matter as a dominant force in galaxies. Contrary to expectations, the universe’s expansion accelerated a few billion years ago, driven by dark energy. This mysterious force pushes matter apart, affecting galaxy formation and growth.

“It’s unclear exactly what dark energy is,” Huterer said. “It may be a new force, or possibly a particle with unusual properties causing the universe to expand faster and faster.”

The early universe was uniform, like a smooth soup, before matter clumped into structures like galaxies. Dark energy counters this clumping by pushing matter apart, working against gravity. If it had been significant from the start, galaxies wouldn’t have formed. Its late emergence altered the universe’s expansion rate and development.

Albert Einstein’s study of pollen particles in water to understand molecular motion is akin to cosmologists viewing galaxies as particles. More galaxies observed improve the analysis of their distribution. The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) team uses clustering patterns to study dark energy’s effects and infer its properties.

Dark energy was first identified through distant supernovae observations, earning the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics for proving the universe’s accelerated expansion. Huterer co-authored the first paper using “dark energy” with Michael Turner.

DESI, a project with Huterer as a key collaborator, suggests dark energy is evolving over time, challenging the belief of constant energy density. The DESI data shows its effect on cosmic expansion has decreased by about 10% over 4.5 billion years.

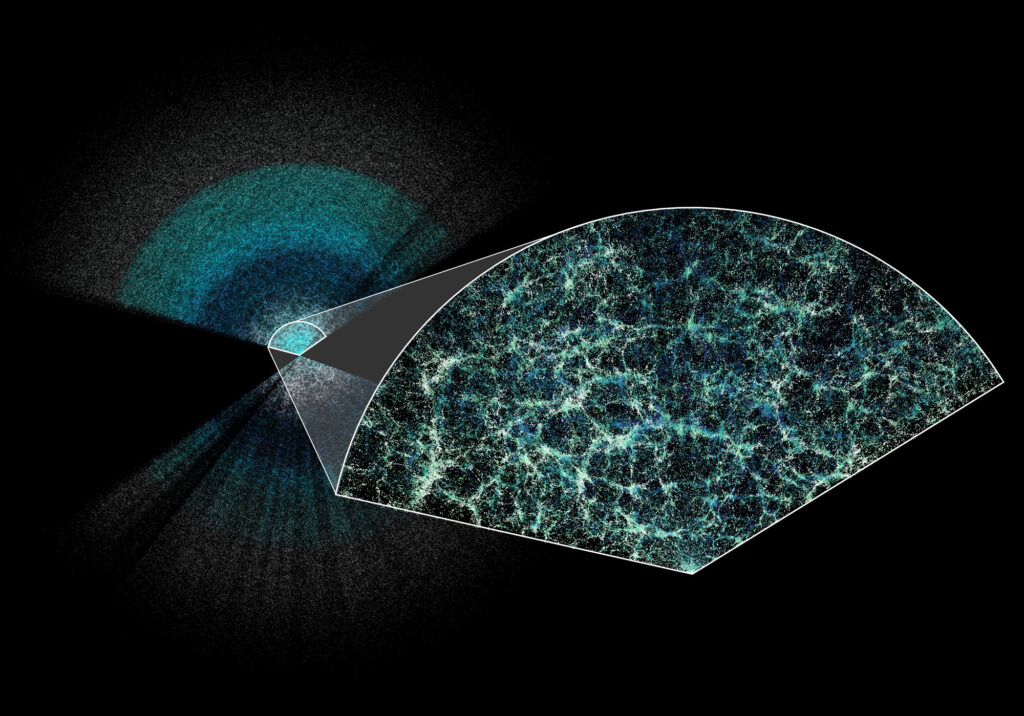

Using advanced spectroscopic mapping and 5,000 robotic arms, DESI measures galaxy and quasar redshifts, mapping the universe’s expansion in 3D. By tracking baryon acoustic oscillations, scientists reconstruct cosmic expansion shifts. Machine-guided observations and computational analyses reveal hidden universe-scale patterns.

The team employs mathematical models of galaxy distributions and statistical techniques to compare them with theoretical predictions. They account for errors and apply machine learning to detect deviations from the standard dark energy model. This integrated approach allows testing cosmological models and exploring phenomena like dark energy decay across cosmic timescales.

“Decades ago, cosmology was a purely theoretical field, led by abstract theories and imagination,” Huterer said. “But since the 1990s, it has become a highly quantitative science, producing vast amounts of data that have taught us so much about the universe. Today, converting observations into results requires a great deal of computation and cosmological simulations, as well as attention to systematic errors in both theory and measurements.”

The DESI project engages around 1,000 scientists to map approximately 50 million galaxies’ 3D positions using Arizona’s Kitt Peak telescope. Once data is collected, the collaboration analyzes galaxy distribution with cosmology-adapted statistical methods. Examining millions of galaxies’ distribution helps identify large-scale patterns and draw conclusions about dark matter and dark energy.

“This work is heavily computational, but based on theory,” Huterer said. “The possibility that dark energy density is changing over time has the scientific community excited. If confirmed, this would be as big a discovery as that of dark energy itself. It’s really wonderful to be paid to work on these exciting developments that help us better understand the universe.”

—

Read More Michigan News