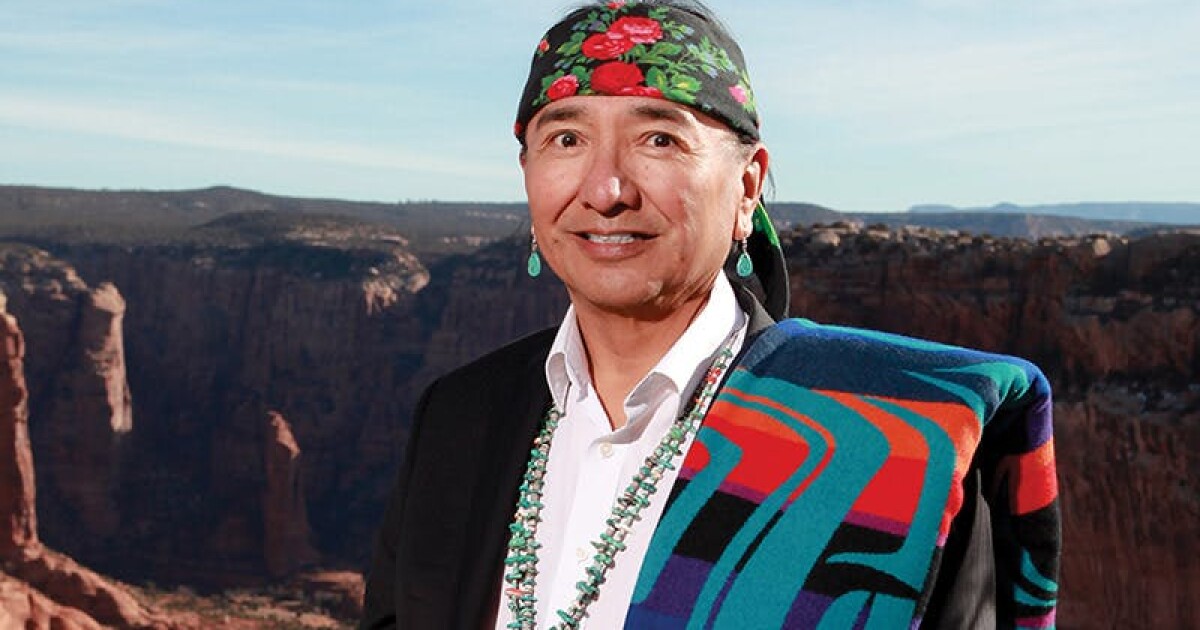

Rogério M. Pinto, born in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, during the 1964 coup, grew up under a 20-year dictatorship. He learned to communicate indirectly through music and art due to the oppressive environment. Now, Pinto is a University Diversity and Social Transformation Professor and Berit Ingersoll-Dayton Collegiate Professor of Social Work at the University of Michigan. He also holds courtesy appointments in the School of Music, Theatre & Dance and the Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design.

“You learned early on that there were things you couldn’t say directly, so we created other ways to speak — through songs, stories and symbols that carried meanings we all understood, even if we couldn’t name them aloud,” Pinto shared.

Growing up poor and queer in Brazil, Pinto later experienced racial and ethnic bias in the U.S. This shaped his work in social consciousness and art. “I have used myriad art forms in social work research and teaching to study and to inspire critical consciousness,” he stated.

Sharing his experience

Pinto, who studied biological sciences and education in Brazil, moved to the U.S. for graduate studies at Columbia University. After nearly 30 years in New York, he joined the U-M faculty in 2015. His classes often involve drawing and engaging in “critical dialogues,” a concept by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire.

Pinto’s teaching draws from Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” and Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed. Freire used pictographs to initiate discussions on societal forces in rural Brazil, while Boal’s theater invited audience interaction. These methods activate critical consciousness and encourage questioning of reality.

“Freire believed that even when people are lied to, they can still recognize the truth if given the chance to reflect,” Pinto said. “And Boal suggested that we should embody those reflections and act them out.”

Art as a teaching tool

Pinto uses art in teaching to foster empathy and self-discovery. “When people describe a painting, sculpture or music, they’re often describing themselves without realizing it,” he explained. This vulnerability fosters empathy. One notable project, The Dream Flag, emerged from a workshop at Brazil’s Center for the Theatre of the Oppressed.

The Dream Flag Project involved painting American flags from memory, posing questions about symbols and meanings. Participants then created new flags representing their identities. “It’s a healing process,” Pinto said. The collaborative exercise led to powerful conversations about identity and inclusion.

In 2024, The Dream Flag was a central project of the U-M Art Collective, culminating in a vibrant event at the SSW’s Impact Awards. Over 40 participants crafted eight collaborative flags, embodying Freire’s ideals of reflection and action.

Art as a means of research

Pinto also uses art to explore trauma and healing. In one study, he collaborated with incarcerated men to address internalized homophobia and sexism. Art facilitated dialogue about identity and power.

An autobiographical monologue, “Marília,” explored family grief under dictatorship and poverty. Performed in New York and South Africa, it blended personal and social history.

“At the end of ‘Realm,’ everyone held a small white box, symbolic of my sister’s coffin, filled with things they’d gathered along the way,” Pinto said about a related performance art piece. This artistic approach merges inquiry with expression, akin to academic publishing.

Up next

Pinto’s outlook remains hopeful despite exploring challenging themes. “Critical reflection is not just about despair,” he said. “It’s about possibility.” Off-campus this term, he is preparing for the May 2026 release of his book, “Freire and Drama: ‘Marília,’ a Play – Anti-Oppression and Healing in the Arts.” The book blends Freire’s theories with Boal’s methods to tackle issues like racism and xenophobia through art and dialogue.

“I hope the innovative nature of this book will engage those involved in the arts and social sciences, particularly social work,” Pinto said. “It will serve as a springboard for artistic research and practice to address contemporary issues such as racism, xenophobia and colorism and move us toward liberation.”

—

Read More Michigan News