In March 1926, University of Michigan students founded the Negro-Caucasian Club to promote equity for Black students. The club’s creation was sparked by an incident in 1925 when Lenoir Bertrice Smith, one of the few Black students, and her white friend, Edith Kaplan, experienced discrimination at an Ann Arbor restaurant. A busboy placed dirty dishes on their table, highlighting racial prejudice faced by Black students both on campus and in town.

Smith and Kaplan noted that, despite integrated classes, Black students were often segregated in housing and social activities. Black men typically stayed in fraternity houses or with Black families, and Black women were barred from dormitories, forcing them off-campus. University facilities, like the Michigan Union, and public amenities, such as swimming pools, excluded Black students.

Seeking change, Smith and Kaplan consulted with faculty member Oakley Johnson, who supported their cause. They approached LSA Dean John Robert Effinger, but he declined to assist. Undeterred, Smith, Kaplan, and other students formed the Negro-Caucasian Club to foster racial understanding and combat discrimination.

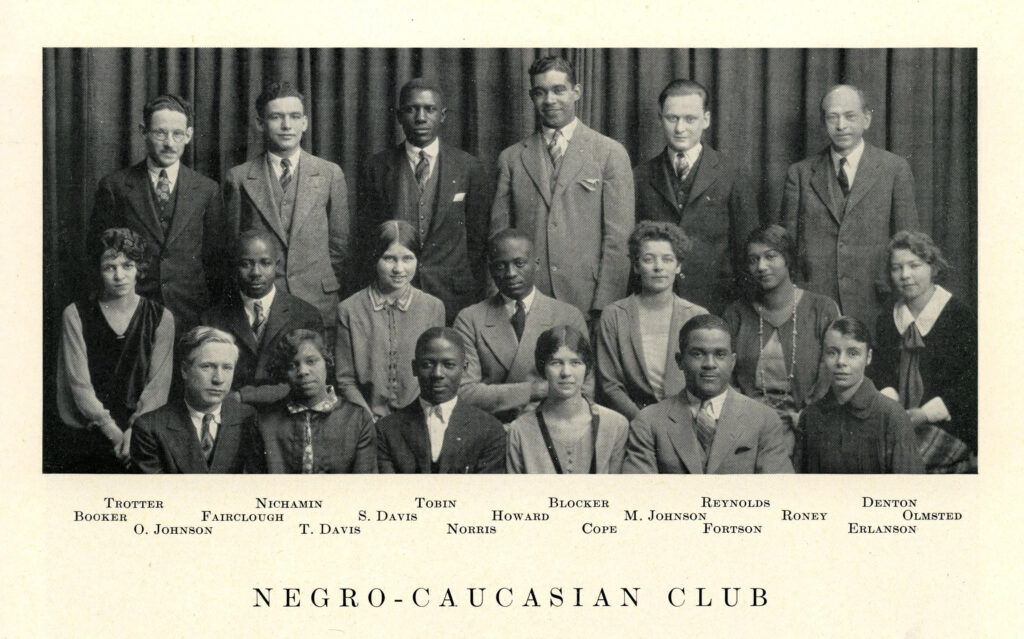

The club’s initial 26 members, comprising 21 Black and five white students, aimed to enhance race relations. Seeking official recognition, the club faced resistance from U-M administrators. Dean Joseph Bursley agreed to discussions on race but discouraged activism. Consequently, the club’s purpose was revised to emphasize “friendliness” and “discussion.” Approved for a one-year trial, they could not use the university’s name.

Despite restrictions, the club pursued a robust agenda. Their first initiative involved surveying white students to uncover stereotypes, revealing ignorance as a key issue. They organized events featuring notable Black leaders like Alain LeRoy Locke, W.E.B. DuBois, and Jean Toomer, and held discussions with figures such as A. Philip Randolph and Clarence Darrow.

The Negro-Caucasian Club expanded its membership and operated for about five years, but the Great Depression led to its decline by the early 1930s. However, its legacy continued through members’ careers in fields like medicine, social work, and journalism. Smith advanced in academia, while Kaplan became a language expert at the University of Chicago.

In 1969, following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, surviving club members, including Joseph Leon Langhorne, reunited in Washington, D.C., to reflect on the Civil Rights Movement and the club’s impact during their university years. Langhorne remarked, “I think the N.C. Club served a distinct purpose then. It was the only forum … for airing of Negro people’s views and students’ problems in Ann Arbor.”

This story was adapted from a story on the Heritage Project by James Tobin, which can be found online at myumi.ch/A1X4g.

—

Read More Michigan News