SUPAI, Ariz. — Kambria Siyuja was always the standout student in Supai. Raised by educators in the tribal village at the Grand Canyon’s base, she outpaced her kindergarten peers. At Havasupai Elementary, teachers often relied on her to tutor younger students, and she even led classrooms at times. Siyuja graduated as valedictorian.

However, leaving the K-8 school, Siyuja realized her educational shortcomings. “I didn’t know math or basic formulas,” she admitted. As she recounted her high school transition to a Sedona boarding school, 150 miles away, tears filled her eyes. Her family cried at the Havasupai Tribal Council, recalling her choice driven by the lack of a local high school.

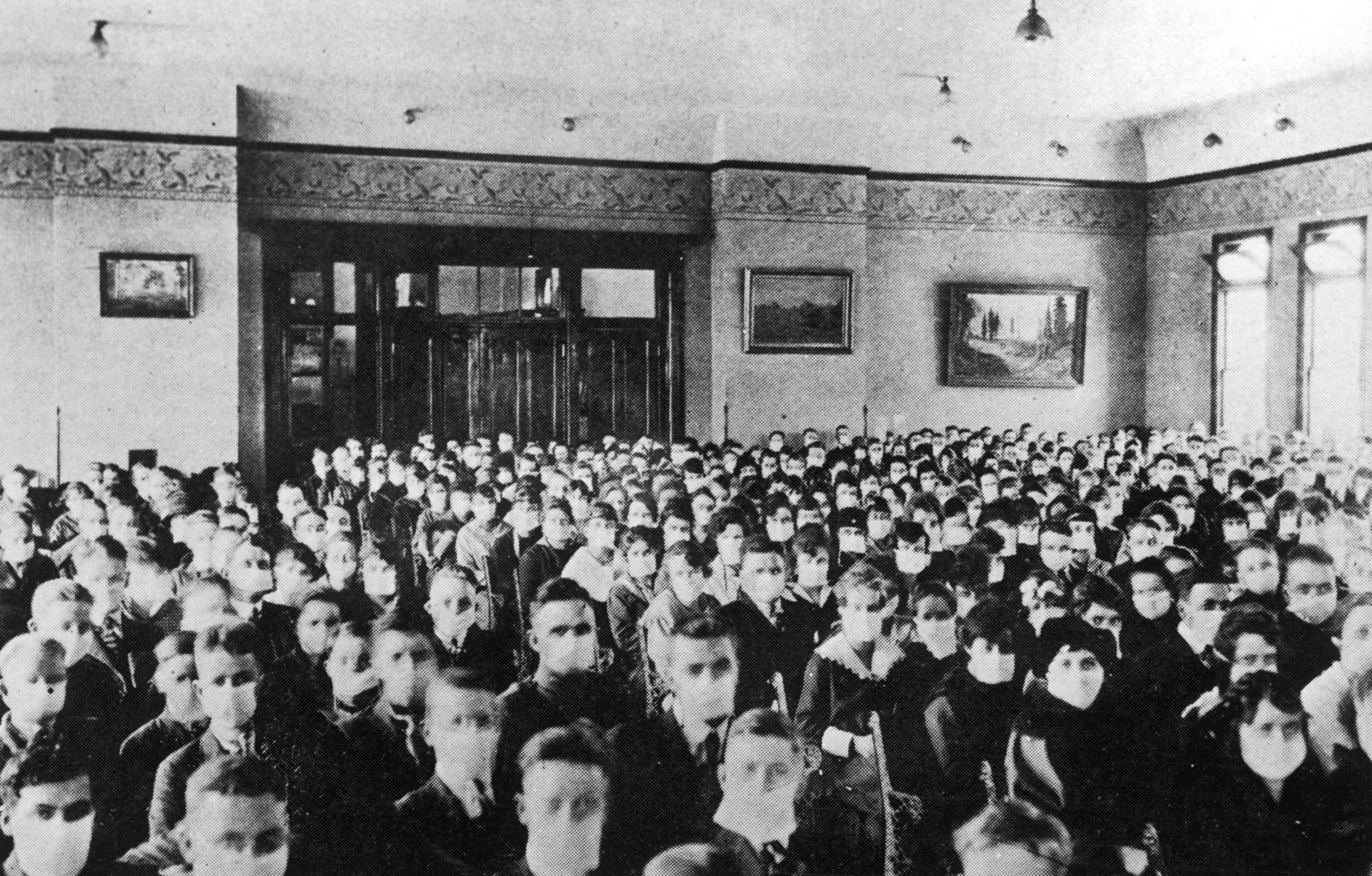

At her new school, Siyuja discovered her education gaps. She had limited knowledge of history and literature and was the only freshman unfamiliar with pre-algebra. Eight years post-graduation, Havasupai Elementary still lacked pre-algebra and textbooks for core subjects. Staffing challenges on the remote reservation meant few educators taught multiple grades. Only 3% of students were proficient in English or math.

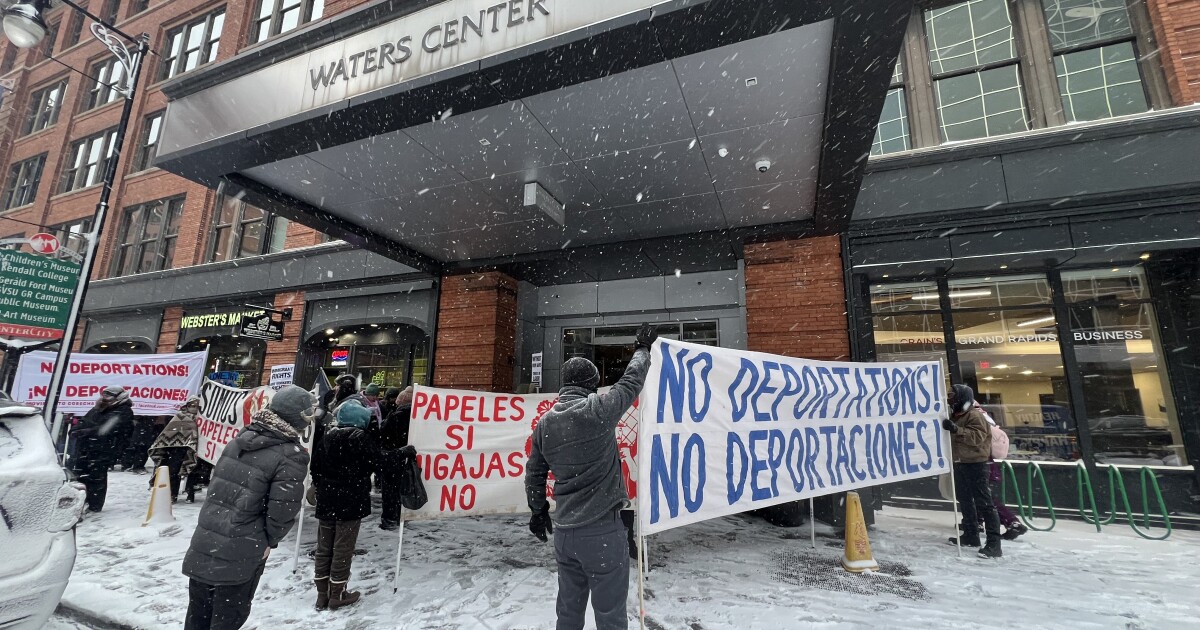

“I know they struggle a lot because of how few resources we have down here,” Siyuja said of Supai, accessible only by an 8-mile hike or helicopter. “But what are they teaching here?” In 2017, six families sued the federal government, alleging the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) denied their children their educational rights. The tribe argued the school was the “worst in a deplorable BIE system,” requiring court intervention.

Historic settlements from the lawsuit brought hope for reform across BIE schools. Supai saw new staff, a reconstituted school board, lesson plans, and a curriculum. A new principal vowed to stay beyond a year. “We now have some teachers and some repairs to the building that are being done,” said Dinolene Kaska, a mother and new school board member. “It has been a long time just to get to this point.”

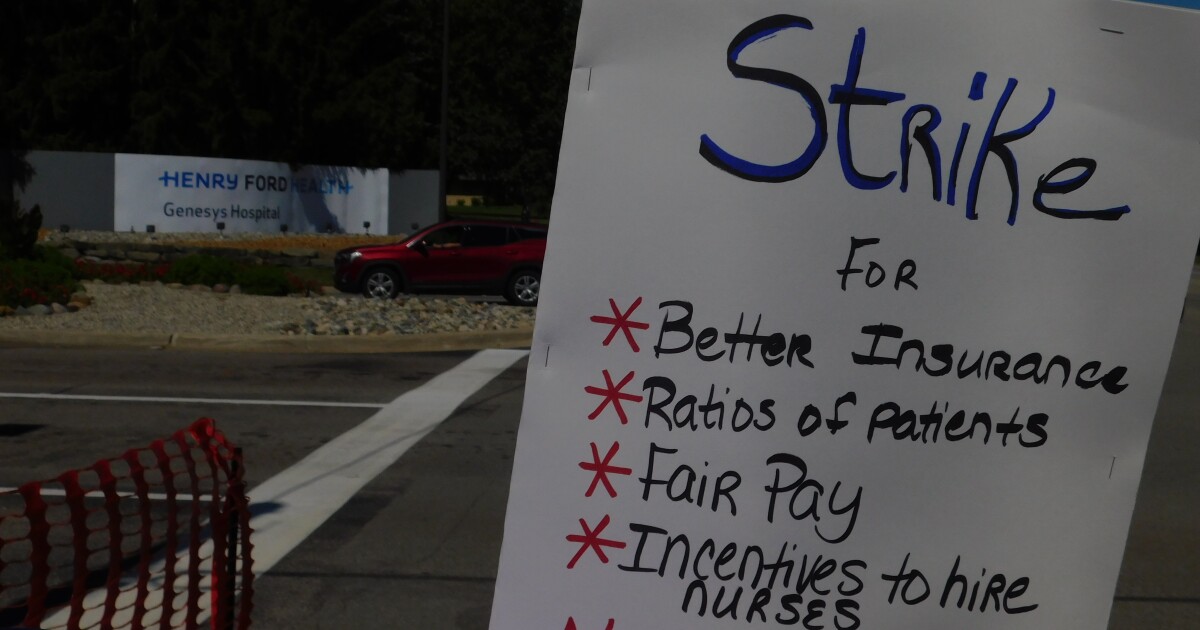

Despite federal efforts to improve the BIE, President Trump’s government restructuring led to worker layoffs, threatening BIE funding and its commitment to tribal education. The administration’s shift towards school choice programs faced criticism due to limited educational alternatives in remote areas like Supai. “Tribes in rural areas don’t have a lot of school choice,” said Quinton Roman Nose of the Tribal Education Departments National Assembly. “For Native students, that’s not a good model. I don’t think it’s going to work for so many.”

Brian Schatz, a Senate Committee vice chairman, criticized Trump’s actions as reckless, aiming to protect tribal treaty responsibilities. BIE Director Tony Dearman defended the bureau, promoting a strategic plan emphasizing tribal sovereignty and cultural education. The Department of the Interior’s oversight of tribal schools faced criticism, leading to BIE’s creation in 2006. Yet, the BIE struggled with federal standards and deteriorating school conditions.

The Havasupai lawsuit highlighted education failures, with insufficient staff and curriculum gaps. Parents noted students’ lack of cultural education and basic knowledge. Kambria Siyuja recalled cooks and janitors substituting as teachers. In 2017, families sued the BIE, citing a federal right to Native education. The government partly acknowledged its failures but blamed logistical challenges.

The case focused on education rights under the Rehabilitation Act. Complex trauma and adversity in Native communities were argued as disabilities deserving educational support. The government warned against linking adversity to learning, fearing widespread obligations. The court’s mixed decision allowed special education claims, acknowledging trauma as a disability.

The 9th Circuit Court allowed the case to proceed, clarifying judicial power over agency compliance. The eventual settlement provided $850,000 for education services, teacher stipends, and cultural staff. The case’s impact on Native education could extend beyond Supai, with potential for broader accountability.

Recent BIE staffing efforts addressed previous compliance issues. New hires filled teacher roles, and curriculum development progressed. Principal Hoai-My Winder pledged long-term commitment to Havasupai Elementary. Despite challenges, community involvement and legal victories foster optimism for educational improvement.

Kambria Siyuja, now pursuing education at Fort Lewis College, plans to return and teach at Havasupai Elementary, aiming to enhance local education. “It’s really weird taking a class in college and learning stuff they should have taught me at that elementary school,” she said. “I just want the younger kids to have a much better education than we got.”

—

Read More Kitchen Table News