Changes in Michigan’s Sentencing Laws Bring New Hope and Challenges

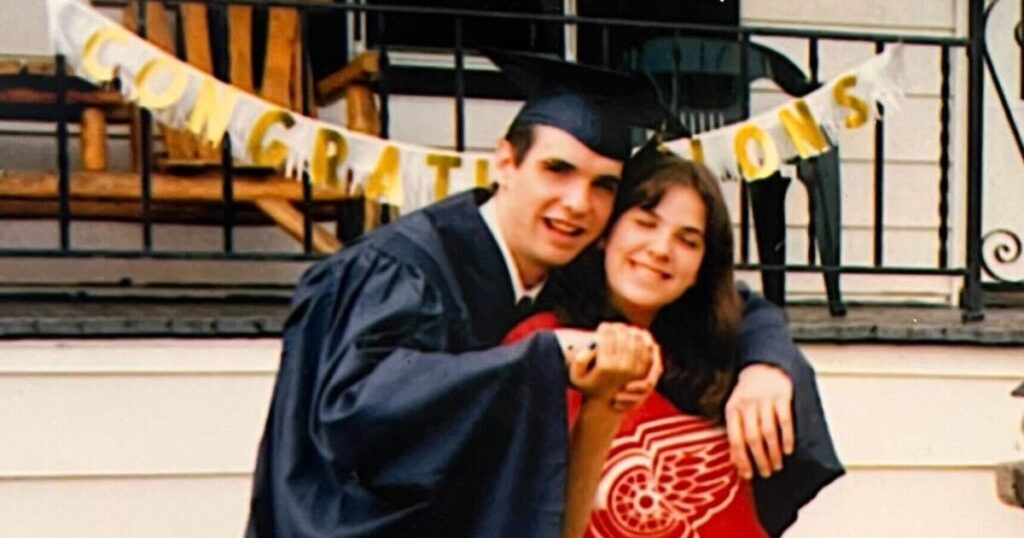

In a state where life sentences without parole were once common for serious crimes, recent legal developments are shifting the landscape for many who were sentenced as young adults. Chris Dorch, once serving a life sentence for a crime committed at 18, is now experiencing life outside prison walls for the first time in over three decades.

Dorch was convicted of first-degree murder at the age of 18 for shooting and killing a man. Under Michigan law, such a crime demanded a mandatory life sentence without parole. Despite the severity of his actions, Dorch recalls, “I knew a lot of these young guys… without excusing what it is that we did, without minimizing what it is that the families went through or suffered because of what it is that we did, I understood there was more to the story than just the act itself.”

In 2016, a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision mandated the reevaluation of life without parole sentences for those under 18, labeling them as “cruel and unusual” due to scientific findings on adolescent brain development. This ruling prompted Michigan to address the cases of over 370 juveniles convicted of murder. Dorch saw a glimmer of hope, believing that the same brain dynamics applied to him and others in his age group.

Subsequent rulings from the Michigan Supreme Court further extended the scope, covering individuals who were 18, 19, and 20 years old at the time of their crime, making over 750 people eligible for resentencing. Dorch, now free and residing in Oak Park, reflects on his release: “It still doesn’t feel like it’s happening,” he shared, acknowledging the ongoing pain of the victim’s family and expressing his own sense of guilt and shame for his past actions.

Pushback from Prosecutors

The progressive changes have sparked a debate in Michigan. J. Dee Brooks, the president of the state’s prosecutor’s association, voiced concerns, stating that extending the protections to those aged 18 to 20 is excessive. “I think it’s quite frankly, a gross overgeneralization, to say that every 18 and 19 and 20 year old brain is not developed fully or sufficiently for them to be held fully accountable for an act of first degree premeditated murder,” Brooks remarked.

These rulings demand prosecutors to decide quickly if they wish to reimpose life without parole sentences, presenting logistical challenges. In counties like Wayne, with nearly 400 cases, the task is overwhelming. Genesee County’s prosecutor David Leyton emphasized the need for sustained resources, stating, “I need more staff. I need more lawyers. I need more paralegals. I need more victim advocates. I need more support staff.”

The Michigan State Appellate Defender Office anticipates decisions on resentencing for 18-year-olds by December 29, 2025, and by January 5, 2026, for those aged 19 and 20. Marilena David, the director of the Michigan State Appellate Defender Office, highlighted the importance of offering a second look, emphasizing the potential for rehabilitation among these individuals.

Despite the potential for resentencing, freedom is not guaranteed. The minimum sentence remains 25 years, and parole board approval is required for release. Notably, many of those eligible for resentencing are already 50 or older.

“I thought we had justice until this happened.”

For families like Jennifer Cline’s, these legal changes reopen old wounds. Cline’s brother, Joseph Knope, was murdered nearly three decades ago. She vividly recalls her brother’s protective nature and struggles with the idea of his killer having the opportunity for resentencing. “I thought that we had justice, and I would never have to see this guy ever again,” she expressed.

Living with Both Freedom and Guilt

Chris Dorch acknowledges the pain felt by families like Cline’s, admitting, “You’re right. We do not deserve it. If it’s a matter of what we deserve, then I’d still be in prison rotting.” Dorch reflects on his past actions, noting that he failed to consider the victim’s family’s suffering during his trial. Over time, he has learned empathy and taken responsibility for his actions, hoping to show that change and rehabilitation are possible.

“I can’t even ask that you empathize with me, but I will ask that you share with me in understanding that change comes because an individual sees himself and takes a position against himself for the wrong that he’s done,” Dorch said. “And that individual is no longer the individual that you knew. He’s someone completely different.”

—

Read More Michigan News